On New Year’s Eve, 1989, Collier Boyle woke up to some strange sounds coming from somewhere in his house; the next morning, his mother was gone.

That’s how Collier recounted the night of his mother’s murder at the hand of his father. A Murder in Mansfield follows an adult Collier going back to Mansfield, Ohio, for the first time in many, many years.

We’re given the background of the murder and the trial at the outset of the film; Mansfield opens with Collier’s willing, almost exuberant, and strikingly mature testimony against his father. Jump forward to the present day. Collier (who has since changed his surname to Landry), now living as a successful cinematographer in L.A., has returned to Ohio for the first time since he moved away. From there, we follow him as he revisits the places and people from his old life, including his father.

A Murder in Mansfield is fascinating and insightful, but only in fits and starts. Collier’s resilience and emotional strength in dealing with the reality of his mother’s death is nothing short of amazing. From his conversations with adopted parents and other adult authority figures (including the detective on his mother’s case) and archival footage, Collier displays more emotional depth than most adults I know. But the way (the very accomplished) director Barbara Kopple has structured the film really hobbles it.

The film is fairly messy from a structural standpoint. It’s very meandering movie, floating from one conversation to the next; from visits to his adopted parents to his therapist to talking about the case and so on. Details and timelines of the murder and Collier’s childhood are unclear; some scenes (such as a visit to the choir group Collier was a part of in high school) seem largely unconnected from a dramatic standpoint, and the pacing generally drags. Most of the film’s flaws are excusable on their own terms, but in aggregate they really take their toll to the point where parts of the movie come across as pointless — which is both astonishing and a downright shame.

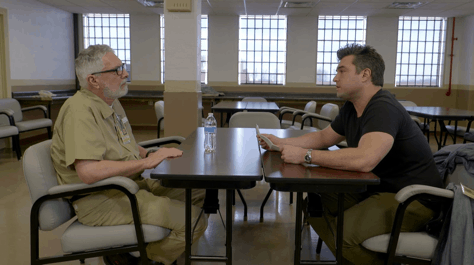

That’s not to say that the film has no redeeming qualities. It’s not bad! It’s just not great, either. To give credit where credit is due, the portrait Kopple paints of Collier is a well-rounded one, giving us a good sense of who he is as a person. And for all the structural faults in the hour or so leading up to it, the climax — Landry’s conversation with his father in prison — is as compelling heart wrenching as you might expect.

Films like A Murder in Mansfield are always the hardest write about. It’s a film whose flaws blunt the impact of what is a very important and emotional journey for a very real human being. So for me, it becomes a sort of crisis of conscience; it might even be a minor crisis of ethics. How do I — or can I — critique a film like this, one so important and personal to its subject, without coming across as callous or cruel or indifferent to lived experiences I have no real concept or basis of? When reviewing a documentary, especially one such as this, by dissecting the film you almost always wind up (intentionally or not) dissecting the lives of its subjects in some way. Or, at the very least, it’s guilt by extrapolation (i.e. “I found x film boring” can be interpreted as “The subject of x film is not worthwhile”).

But to say that A Murder in Mansfield left me mostly unaffected is not a shot across the bow at Collier Landry, nor is it meant to discount or mitigate the personal importance of his journey. Instead, to say that A Murder in Mansfield left me mostly unaffected is an expression of my disappointment in what probably could and should have been a film of such emotional depth and feeling.

The film had its world premiere at DocNYC 2017 today.