In a time when American school shootings have become routine, “Tower” is a strong reminder of the wounds that horrid events like this leave behind.

Since that sweltering terror-filled August day in Austin, there have been over 200—that’s right, 200—school shootings in America. Over 150 of them have occurred in the 21st century alone. With statistics like that it seems almost negligent not to address the issue in some sort of overhaul. But instead innocent people continue to die in an asinine manner that could easily be avoided with legislation to reform gun control. And with over 30 percent of Americans owning a gun—with about 3 percent of them owning more than half of all guns in the US—it seems that it will be a while before we see any kind of real change.

Tower tells the haunting story of the 1966 Texas of University at Austin mass shooting through the perspectives of several survivors and bystanders as they recount that harrowing day that changed them forever. And even though the events occurred over 50 years, the survivors choke back tears and break their voices as they retell their experiences that dreadful day.

At the time of the shooting, people worldwide could hardly believe that such a horrific mass school shooting could occur. Until then there were seldom any mass murders that occurred in schools. The term “school shooting” had never truly existed as we know it today up until that time. In 1966, it was a newfound phenomenon, one that Charles Whitman had helped begin—a figure that director Keith Maitland wisely does not focus on in his moving documentary about the people who lived to tell their stories.

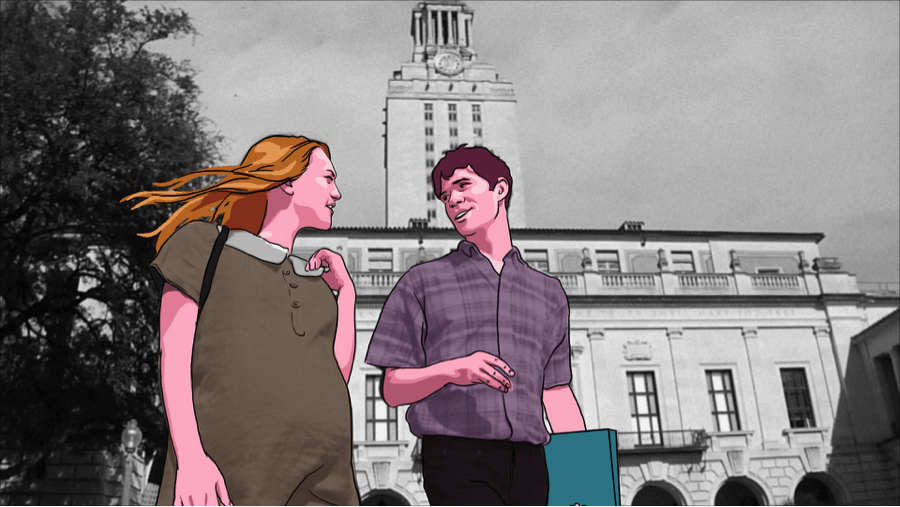

Mixing present-day narrations with reenactments in rotoscopic animation, Maitland creates an invocative anachronistic image that beckons the viewer to relive both the past and the present through the eyes of the survivors. By using the Scanner Darkly-inspired stylization, Maitland does an excellent job of demonstrating the sheer lunacy of the incident at the time of the shooting. Meandering between monochromatic and color animation, the director details the emotional state of the individuals in question with powerful purpose. What emerges is a telling documentary that focuses exclusively on the survivors and their remembrance of the worst day of their lives.

But while the formally astute film does a stellar job of journalistically recounting the hour-long ordeal, it does so in a somewhat gauche manner. By using actors to narrate the events as if the interviews were held a mere few months after the episode, there seems to be a discernable distance that emerges between audience and narrator and a lingering sense of emotional inauthenticity.

Not to say that reenactments are bad or cheesy—Errol Morris’ excellent The Thin Blue Line has certainly proven so—but the way in the film attempts to detail the emotional state of the survivors through editing feels forced and thus loses some of its emotional value. It’s a device that leaves one wondering why Maitland did not just have the real survivors in present-day relate the story, as they end up doing by the end of the film. Perhaps it did not work stylistically or would have seemed unoriginal to do so, but had Maitland kept the rotoscoped reenactments separate from the real-life interviews then perhaps the fragility felt by the police, bystanders and survivors would have that much more pronounced. Perhaps it would have more aptly pointed out the insanity of the ubiquitous nature of school shootings today.

While that may seem to be more in line with documentary puritism, it does not sabotage the film. In fact, the effect works well on a narrative level. By creating an osmosis between the present and the past, we are led down a heart-pounding and touching plot where each survivor’s story meanders into the other. From the salesman-turned-deputy to the heroic law student, each subplot works to create a cohesive web that showcases the natural drama and suspense of such a malevolent situation. Particularly as it was the first shooting of its kind—but unfortunately not anywhere near the last.

While the film’s sense of urgency comes to be more pronounced toward the final act, it unfortunately does so in a lackluster manner that relies on a quick montage of the last few headline-grabbing mass shootings, feeling rushed and thematically unexpected. But perhaps that is a good thing, as a redirected focus on the foreshadowing of the 1966 event to today’s would only serve to derail Maitland’s attention on the UT Austin mass shooting.

In the end, Tower is an outstanding look at the plight, psychology and thoughts of mass shooting survivors. And perhaps what is most harrowing about the film is that most of the individuals, whether they were on the campus or reporting it from afar, are still deeply shaken by the incident. In an age where school shootings are occurring at a growing frequency, the viewer is left wondering how the survivors of today’s mass shootings will cope in the future. If Tower is any indication, it tragically seems not all too well.