What do you make of a play that doesn’t know who its audience is?

Angry Young Man, opening this week at Urban Stages, tells the story of a Yussef. He’s an immigrant from an unnamed Middle Eastern country who has sought refuge (and a job) in London after a botched surgery (“Malpractice makes perfect!” he comforts). Yet more than anything, his story feels like a modern Midnight Cowboy. Like Joe Buck (Jon Voigt) in John Schlesinger 1969 Oscar winner, Yussef arrives in the big city hopeless out of place. A mix up with the cab company relieves him of all of his money. Filled with visions (or delusions) of grandeur, he’s stuck with no friends, family, or cash and a limited amount of English before a chance encounter with Patrick, a young revolutionary, complete with red-starred cap, pulls him into the London underworld.

Comedy ensues.

Or at least enough to quiet the audience. The chatting woman behind me were annoyed before the play even began, an actors flashlight causing them to exasperatedly complain. Up front were a group of boys who had apparently come for a birthday party, and it only took one rebuke from their mother— “Put that phone away!”— for them to quiet down. Before long they were laughing aloud.

And make no mistake, despite what the title might imply, Angry Young Man is funny. Christopher Daftsios (listed as Actor D in the playbill) is relegated to fiercely mugging for the audience, acting out everything from a dog to a mounted stag. The rest of the actors seem to take an almost perverse delight in describing a scene and then watching him hurry about and bending himself into odd shapes, his tongue frequently falling out of his mouth.

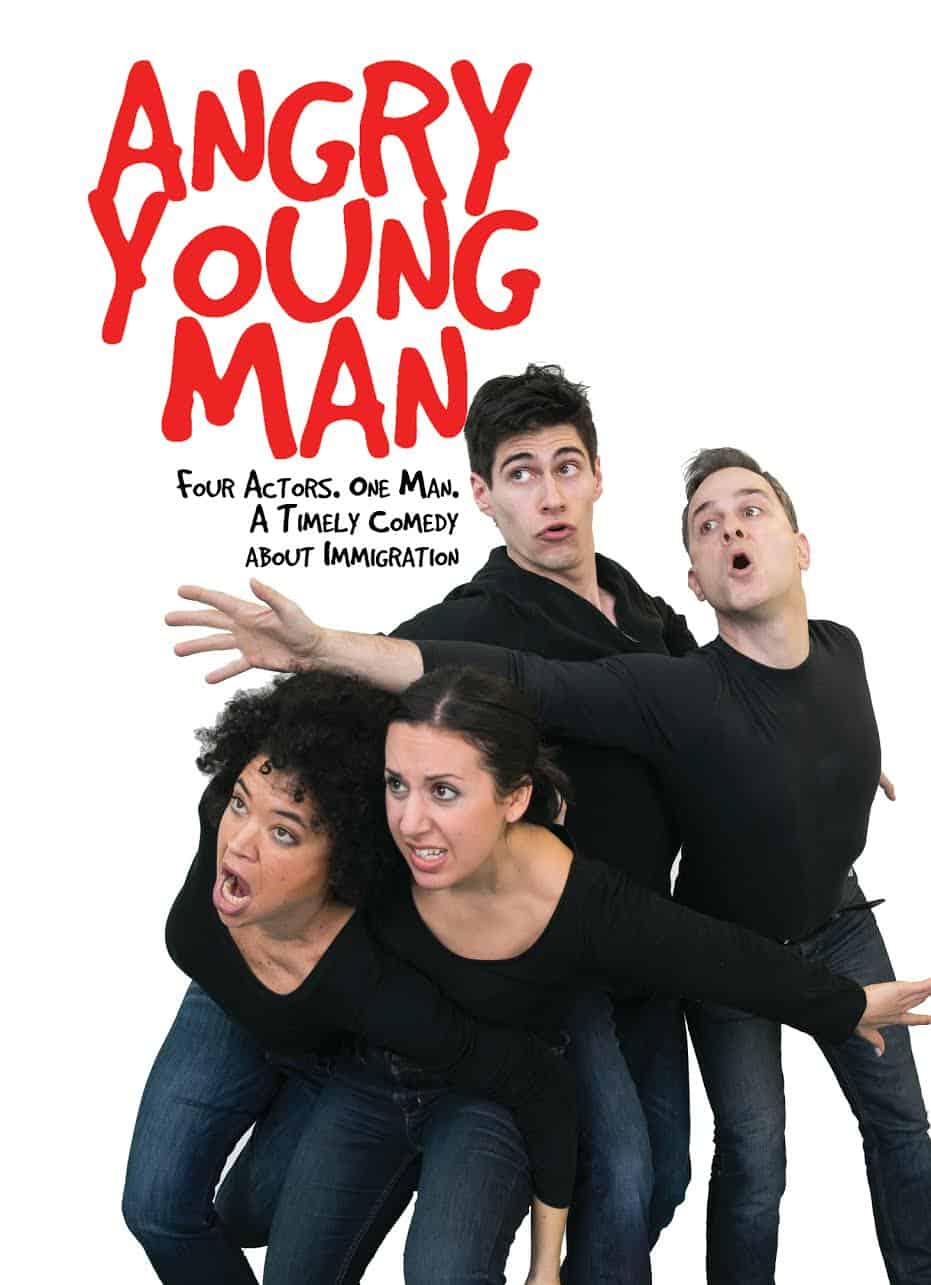

The central gimmick here is that Yussef is played by all four members of the cast (Christopher Daftsios, Rami Margron, Max Samuels and Nazli Sarpkaya), tagging in and out and different times as they do the incredibly difficult job of balancing him with the rest of the weirdos he encounters in the London underworld. This never quite gets old, each new scenario Yussef is thrust into bringing with it the logical question of how he’s going to get out of this one. Accidentally kill a neo-nazi? Uh oh. Fall in love, or rather lust, with your new friends belle? Yikes.

Everything in Angry Young Man is played broadly. Max Samuels pulls double duty as both our hero and a femme fatale, the transition marked by the comically over exaggerated ripping open of his shirt. Even the oversized, double breasted suits worn by each actor engulf them, rendering their collective Yussef ungainly and comical, as though his discomfort in this new world has seeped into his very being.

His discomfort is tangible. Swallowed by their costumes, each of the four actors on stage embody his bumbling, awkward persona. Like a kid who has dressed up in his dad’s clothes, the Yussef that blunders around on stage comes across as a hapless child desperately imitating an adult.

Yet as indignities continue to pile up, it becomes clear that Angry Young Man isn’t sure how it feels about Yussef or other immigrants like him. The desire for a better life is a constant, but even Yussef is played broadly, an unearned braggadocio frequently undercut by the realities of his situation. We sympathize with him as life continues to pile on, from sleeping in the rain to being pooped on by ducks to being cheated by the people that he thought were his friends.

However the constant humiliations are mined for cheap laughs as opposed to legitimate pathos. The result is that by the end of the film, it’s hard to tell exactly how you’re supposed to feel. Because despite its obvious humor and well intentioned message, Angry Young Man often comes across as confused. It wants to take aim at well-meaning but ultimately self serving liberals, like Patrick, who refer to Yussef as a project, a prop in their ultimately bourgeois attempts at revolution. Che Guevara is reduced to a punchline, the Left presented as aloof and ineffectual.

At the same time Yussef is frequently presented with the real threat of violence, especially once Patrick turns him over the skinheads he pissed off. The play wants to have things both ways. Neither side is good, and while this might provide exponentially bigger stakes for Yussef to navigate, it results in a play that feels thematically muddled.

It is not until the final moments that anything like a genuine, human moment occurs. Earlier Yussef encounters a young man, an immigrant like himself, who fled his home country after a local gang took an interest in him. He’s turned 18, and now the UK wants to kick him out. Unfortunately, stories like this are all to real, and just in like real life, Angry Young Man offers little resolution.

Ultimately the play ends with a call for peace. People, Angry Young Man, require help and understanding. Adults might find this saccharine and the moralizing might come across as simplistic, but given the play’s broadness, one is left hopeful that the well constructed humor welcomes a younger audience with whom its message might still resonate.

In the end, Angry Young Man cannot figure out who it’s for, children or the parents that brought them. Nonetheless it proves entertaining enough, just topical enough, to remain endearing. And that’s ok.