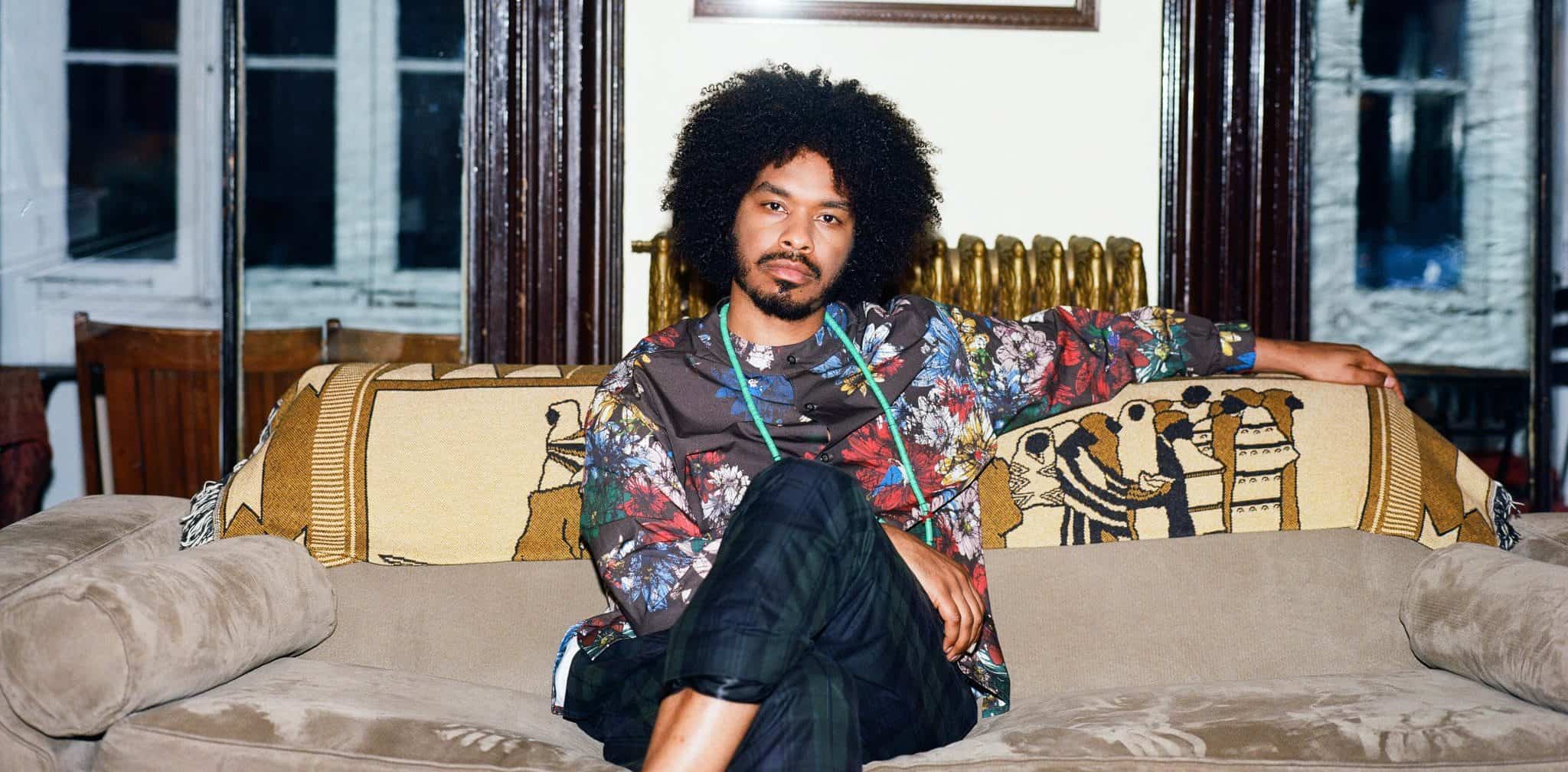

The director and producer of this new HBO series gave us the inside scoop on last Friday’s pilot episode.

Black life cannot be dwindled down to the tidy, constant images of violence we see on the news. Those reports of black men and women shot dead by the police – while harsh realities – are not the only narrative. In his new HBO series, Random Acts of Flyness, artist Terence Nance is also exploring those stories that don’t get enough love. From Black sexuality (its slang, queerness, and passions,) to Black Thought’s own black thoughts (on bathrooms: “They need to install Shea butter dispensers beside the exits,”) Random is a comprehensive, surrealist, and often playful embrace of the Black experience.

The show sees Nance taking a choppy array of film tactics and delivering them under an HBO gloss. Vivid stop-motion cartoons, cuts of media coverage, Claymation, professionally shot faux infomercials, and talk-show segments all converge to create the series’ pilot episode. If it sounds overwhelming, it’s because it initially is— Random Acts of Flyness presents Black life in a way that we aren’t accustomed to seeing, but we can certainly be grateful for it.

The Knockturnal had the chance to attend a Q&A panel with Terence Nance, where he answered interviewers’ questions about this first episode and gave a rundown of what we can expect. Get the inside scoop and catch up on the first episode of Random Acts of Flyness below.

Random Acts of Flyness airs every Friday at midnight on HBO.

This is such a beautiful project and it’s incredibly visual, but how did you explain it and sell the idea to let networks know what they were getting into?

Terence Nance: I didn’t really explain it. The first time I wrote anything on it was in 2006. At the time, it was called “Random,” and the description of the show was essentially what it is now. It didn’t get going until Tamir [Muhammad, collaborator] called me. He was like, “I want to do a TV project,” and I think his specific question was, “What would a new show look like from you?” I was like, “I would never do that!” [Laughs.] But I was like, “I have this thing I want to do, and it’s called “Random Acts of Flyness,” and it would be this.”

What Tamir brought to it was some money through 150 to create the approval concept, and the approval concept was essentially the first half [of the pilot episode.] A lot of it was stuff I had already made, pieces and ideas that I wanted to fit in. I had the opportunity to put it together, so I did. I don’t think we talked about it to anybody without having half of the pilot to show, because I think we all knew it would’ve been impossible to talk about.

When it came down to actually finishing the pilot, we were very clear that we were shopping it around and we didn’t want to develop anything; we would make a pilot and then they could tell us if they wanted to do it or not. I think just insisting upon that made it clear that we were going to put ourselves in a position that only showed what we wanted to do as opposed to talking about what we wanted to do.

Could you talk about that final blackface sequence? What was the process and the energy behind creating that segment like?

Terence Nance: I don’t remember when that idea came about— it must’ve been pretty early on. I was just thinking about language and semantics, and the idea of taking back the word “blackface.” It’s just so… I mean, I have a black face [laughs.] I’m in blackface. So, I was just thinking about reclamation.

We shot that at the Utica stop around the corner from my house. I didn’t really think about the fact that I was going to ask people to say “blackface” on camera before we were doing it, and if they were going to have any adverse reactions. But people were smiling – I didn’t ask them to. Nah, they were just like, “blackface, what’s good?” [laughs.] They were emoting as they would naturally when interacting with people who were there: everybody who was shooting was kind of from the neighborhood. I don’t think anybody felt like there was any kind of point that we were attempting to make, I think we were just attempting to have a platform for people to be who they are. And that’s the act of reclamation, is being.

How do you want white people to take this in and digest it?

Terence Nance: I don’t know, I mean… [laughs].

I’m watching this and one of the things that just came to mind was like, blackness is so bad. It’s just so much. But if I were white, I would be like, wow.

Terence Nance: Well I would ask you a question back: do you really think you would know what it’s like to be white?

That’s a very good retort. I don’t know what it’s like to be white, but I know that if I were watching this, I would be intrigued, but nervous for a point of entry. So my question is: what are your hopes when a white person watches this?

Terence Nance: I don’t even think about that. But I mean, I guess in the abstract, white people listen to Wu-Tang and love it. So, when you ask that question, it’s like, I don’t expect there to be an issue in terms of entry point.

How do you build a series when it seems so based on streams of consciousness?

Terence Nance: I think what I’m hearing in your question is the implication that streams of consciousness are inherently non-linear and non-narrative, and I would say that they’re the opposite. I think streams of consciousness are post-linear and causal. There’s a causality relationship between everything that’s happening. In the pilot and in the rest of the season, there’s a relationship between all the events that happen. And if you are experiencing them linearly, there’s still a non-linearity to either the emotional or tonal experience that’s happening. But it’s all still a narrative experience.

To that point, I think that hopefully the show plays like Game of Thrones. Like, when y’all write about “Please don’t spoil the Red Wedding,” you know what I mean? [laughs]. Don’t try come at it as if it’s sort of a grab-bag of things, because I think our goal is to further the sequence of events to have interrelated moments, happenings, that are kind of dependent on what our experience in life is: going from not knowing to knowing on a moment-to-moment basis.

As artists addressing issues such as violence, how do you balance or ensure that it’s healing and not a sense of re-victimization?

Terence Nance: I think I should toss that to somebody else. But for me, I would say that I don’t think it’s possible to know if someone will be traumatized or re-victimized. I think that our hope is that that isn’t a part of the process. But it’s a risk.

A: Just echoing that, I think it has a lot to do with the energy that you bring to the process as well. Intention is everything— you can have good intentions and [still] go the wrong way. But in the process of making “Everybody Dies!” with Frances [Bodomo,] we were very specific with what we were at least trying to do, and I think going in with that kind of intention can, at the very least, protect against exploitation. But when you’re dealing with heavy concepts and images, there’s the possibility that somebody will, nevertheless, feel a negative emotional response. That’s just a fact of life.

How do you get from the point where you say “I want to talk about this issue,” to how it’s depicted here?

Terence Nance: Well, I don’t think our process is theme first. I didn’t feel that way when we were making it or conceptualizing it. I think it was more like, from the chest as opposed to from the brain. So when you ask, “how do you come to the way you’re going to present the idea,” I think maybe the way kind of comes first a little bit. At least for me, my experience of being with the collaborators was more like, just thinking about the stuff we wanted to make in a way that was not super self-conscious about what it was, and then organizing it later.

Are you happy with the finished product?

Terence Nance: I don’t know that happiness exists, but I’m excited. I think excitement exists. I’m excited— I’m very excited… And I think it’s done! [Laughs].