In 1967, much of America was swept up in what became known as the Summer of Love. But in Newark, that summer looked very different.

For five days, the city was engulfed in civil unrest that left 26 people dead, injured hundreds, and caused millions of dollars in damage. Entire neighborhoods were scarred. Businesses were destroyed. Families were forever changed. Nearly six decades later, the aftershocks are still felt.

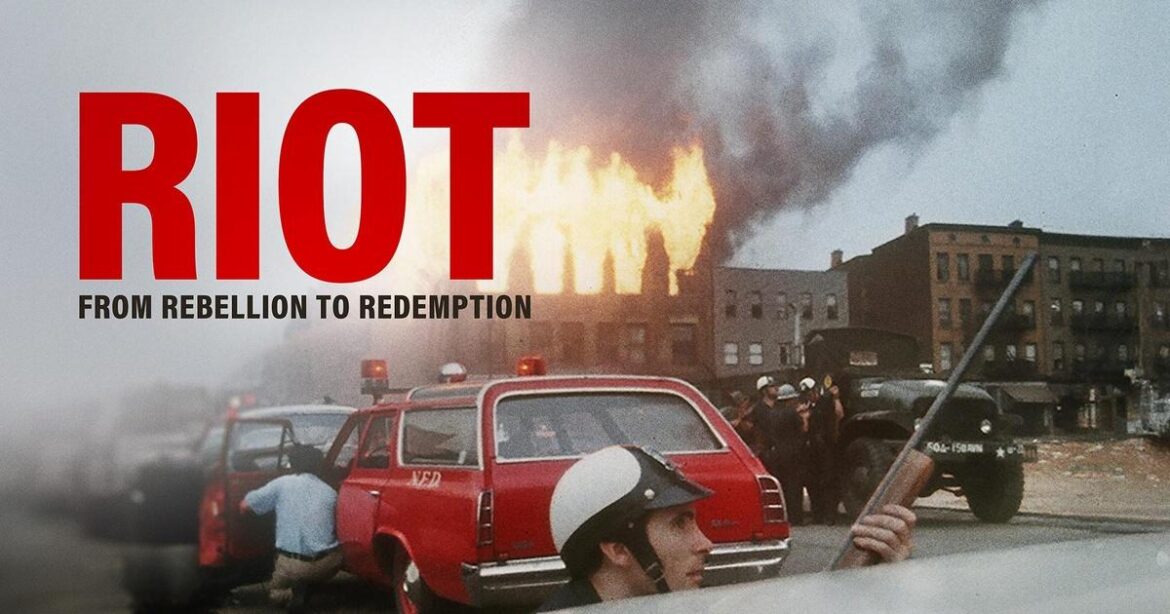

That is the focus of RIOT: From Rebellion to Redemption, a new documentary directed by PBS and New York based filmmaker Kevin McLaughlin. The film begins streaming on the PBS App on February 1 and airs on World Channel on February 12. Through firsthand accounts and interviews with state and local leaders, including Cory Booker, the documentary revisits one of the most painful chapters in Newark’s history and examines how the city continues to wrestle with its legacy.

McLaughlin does not frame the film as a distant history lesson. Instead, it feels immediate. The documentary brings viewers face to face with the racism, systemic inequality, violence, and heartbreak that fueled the uprising and shaped its aftermath. It also highlights the resilience of residents who refused to let the worst week in the city’s history define its future.

When speaking with The Knockturnal about the project, McLaughlin acknowledged that simply getting the film made was an uphill battle. Like many independent filmmakers, his biggest obstacle was funding. Documentaries have long depended on grants, and in recent years those grants have become increasingly difficult to secure.

“Raising the money took persistence and a lot of creativity,” he said. “With the help of some generous friends and an anonymous donor, I was finally able to cover the licensing costs and get the film finished for a proper release through PBS.”

But financing was only part of the challenge. Tracking down the right voices proved just as critical. McLaughlin said one of the reasons he chose this subject was personal. He grew up in the shadow of the 1967 unrest. His father served as a firefighter in Newark during that era, which gave him access to people who had lived through the violence firsthand. First responders, activists, and longtime residents all became essential to telling the story with authenticity.

“You need access to the right people,” he said. “The police officers and firefighters were easier for me to find. But tracking down longtime residents, the people who actually lived there during those days, that took some real searching. And finding former politicians, including mayors from the 70s and 80s, required a lot of digging.”

Their testimonies anchor the film. Viewers hear from those who witnessed buildings burn, who tried to keep the peace, and who spent decades rebuilding their neighborhoods. The result is a layered portrait of a city in crisis and a community determined to reclaim its identity. As McLaughlin continued reflecting on the making of the film, he described the lengths he went to track down one former elected official who had largely stepped out of public life.

“He was elected around 1970,” McLaughlin said. “He wasn’t in hiding or anything, but he was older and out of the public eye. He didn’t use email, so I had to talk to what felt like a thousand different people until someone finally said, I know where he is, I can reach him. Once I got in touch, his wife helped coordinate everything. They were happy to participate.”

That interview, he said, became one of his favorites.

“He’s at that point in life where he doesn’t care what anyone thinks,” McLaughlin explained. “He’ll just say exactly what he believes. That’s the dream for a documentary filmmaker. You want people to be completely honest.”

Honesty, however, often came with contradiction. Early in the process, McLaughlin noticed a striking pattern in the interviews.

“One of the first things I realized was that if you ask ten people the same question, you get ten different answers,” he said. “And when it came to race, there was a clear divide. Many white residents remembered it one way, and many Black residents remembered it another way. So I decided the best way to tell the story was to include all of those voices and let viewers decide where the truth sits, somewhere in the middle.”

The filmmaking process also came with technical setbacks. Some of the archival footage he had hoped to use was lost. When it came time to gather certain clips, he realized a portion of them were gone, material that may never resurface.

Other materials had to be painstakingly restored. Much of the original news coverage from 1967 was shot on film reels. In those days, crews would film during the day and physically cut the reels into segments for the evening broadcast. Decades later, some of that footage had been sitting in storage cases and briefcases, requiring careful cleaning and repair before it could be used.

In total, McLaughlin recorded more than 50 hours of interviews. Many compelling stories ultimately did not make the final cut simply because of time constraints. While the one hour broadcast version airs on PBS, a longer director’s cut running about an hour and 20 minutes is also available for viewers who want a deeper look at one of Newark’s most defining and devastating chapters.

Nearly sixty years after the unrest, Newark is still grappling with the consequences of that week in 1967. RIOT: From Rebellion to Redemption asks audiences to confront that history honestly while also recognizing the endurance and strength that followed.