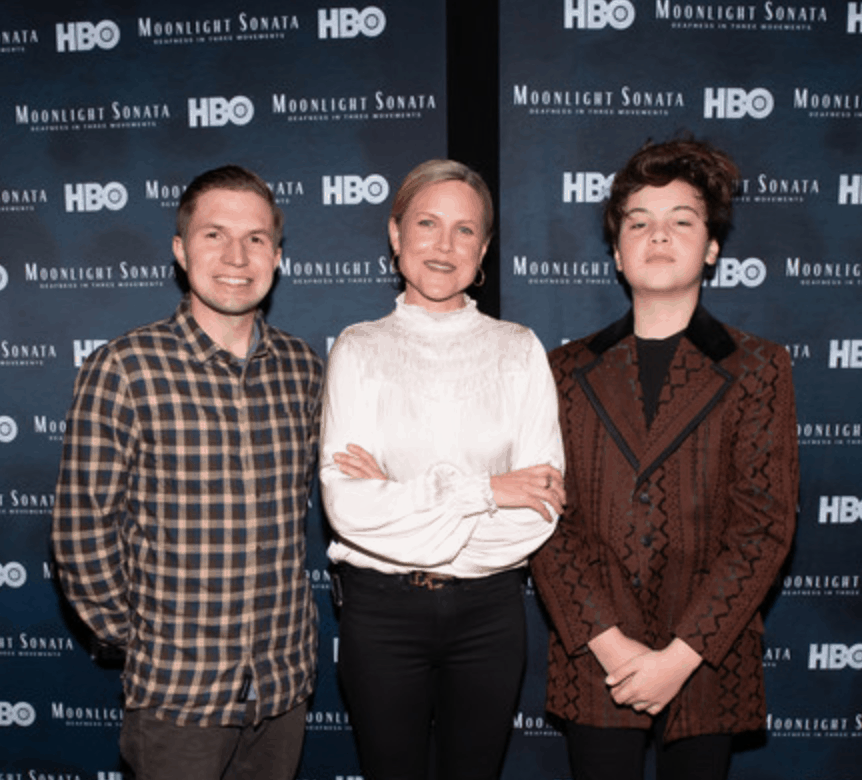

The Lincoln Center hosted a special screening of Irene Taylor Brodsky’s documentary “Moonlight Sonata,” set to premiere on HBO December 11th at 9PM ET.

Irene Taylor Brodsky’s Moonlight Sonata expounds upon the unique synergies between film and music when these mediums are used to tell a story. Brodsky’s latest feature documentary examines her son Jonas’s experience of losing and regaining his hearing as he determines to learn the first movement of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” a piece the composer wrote while processing his own loss of hearing.

Brodsky explores the generational effects of deafness, introducing us to her parents (stars in their own right in Brodsky’s Peabody Award winning documentary “Hear and Now”), both of whom grew up deaf and decided to get cochlear implants together in their sixties. While Jonas is discovering his own voice through a disciplined observance of Beethoven’s musical composition, Brodsky’s father, Paul Taylor, is experiencing a profound loss of self, brought on by an agonizing diagnosis of dementia.

Brodsky positions the documentary in three parts; the use of home videos, interviews, off-screen narration, and observational scenes of family life all serve to elevate the highly personal nature of the narrative. Mother chronicles a son’s relation to sound from baby to boyhood: we witness the degradation of Jonas’s hearing and subsequent speech at a young age, accompanying him on trips to audiologists and speech therapists, as well as getting insight into the rehabilitation that comes after the two surgeries he undergoes for cochlear implants. Throughout, Brodsky skillfully explores the disorienting effects of losing one’s hearing, often employing a soundtrack meant to imitate these experiences with muddled, submerged speech and unevenly adjusted volumes that replicate the tinnitus and ringing that often comes with this process.

We begin to understand that while the reemergence of sound for both generations allows for clearer communication, often times a respite from a noise polluted world is not only a relief but a benefit – not withdrawing into an isolated space, but rather that of solace and comfort. Calling it his “superpower,” Brodsky shows Taylor in one scene take off his implants to retreat from a wailing grandchild, and we witness Jonas learning the same method when his senses are overstimulated. In certain ways sound can be as valuable as its absence.

While the documentary is steadily imbued with the spirit of optimism and wonder, often surrounding the family’s aptitude for music, it can be just as devastating. The latter part of the film focuses on Taylor navigating a world in which he is beginning to lose his mind – depicted in heartbreaking scenes such as when Brodsky informs him she is no longer comfortable with him driving her family. Yet while Taylor descends into a more permanently confused state, he is often still buoyant with joy and love for his family, voicing appreciation for the full life that he has been able to live.

While Brodsky – in voice-overs and on camera – navigates the challenges Jonas and her parents face because of their deafness, she further interrogates what it means to be deaf. She considers how deafness has shaped her family, and allowed them access to a unique connection with each other and with themselves, in ways that those without deafness cannot relate. She notes that when her parents decided to get cochlear implants, they ended up regarding newly discovered sounds as not as meaningful as expected. This intimate portrayal of a family reveals how an impairment can be interpreted as a gift – just as Brodsky argues that Beethoven wrote Moonlight Sonata not in spite of his deafness, but because of his deafness.

In a film that could have been excessively wrought with metaphors surrounding the parallel experience of composer and student, Brodsky gracefully harmonizes the two storylines, presenting Beethoven just enough, as an animated hand directing the audio and visual aesthetic of an ensuing soundscape, or as a bird flying above a darkened ocean, notably apart from his flock. Brodsky succeeds with an abstract and colorful nature of this portrayal, movements that are grounded in the undulating ebb and flow of a singular wavelength.

Hunter Noack performing at the David Rubenstein Atrium. Noack invited the audience to place their hands on the piano to feel the vibrations of the music while he played.

In partnership with the Lincoln Center, HBO hosted the screening in the David Rubenstein Atrium, a performance space that is free to the public and fully accessible. Their programs are supported with braille and large print information, assistive listening devices, as well as real-time open captioning and ASL-interpretation for all viewers. After the screening the audience was treated to a performance by Jonas Brodsky and Hunter Noack, a pianist who performed all of Beethoven’s original sonatas in the film.